October 30-December 16, 2012

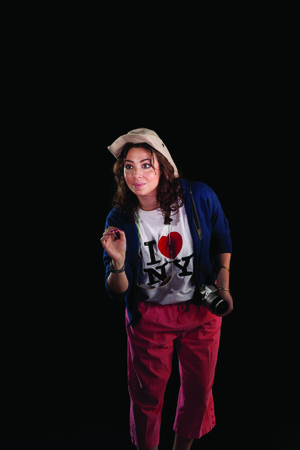

MetroPAL.IS., the creation of the contemporary artist Shimon Attie, is presented in an oval configuration of eight video screens with the viewer standing within the oval. The artist’s intention is for the artwork to re-imagine and re-configure the seemingly intractable Middle East conflict between Palestinians and Israelis by engaging their shared secondary hybrid identitythat of being New Yorkers. In many ways, the artwork is as much about what it means to be a New Yorker, to live in the United States, and to have a layered identity as an Israeli or Palestinian as it is about conflict in the Middle East. The artist invited twenty-four members of both communities, of various genders and occupations, into his studio to be filmed individually. They reflect in pairs not only their Palestinian and Israeli identities, but comparable occupations and conditions. Each participant read a scripted part from a hybrid document that Attie created, that merges the Israeli Declaration of Independence from 1948 with the Palestinian Declaration of Independence from 1988. When a few obvious key signifiers are removed, it is remarkable how much the two documents overlap and mirror each other. MetroPAL.IS. has been crafted and edited such that, like a Greek chorus, there are times when only one individual is speaking, or two, or eight, or none. Attie conceived of the piece in musical terms, with the relationship of individual voices being thought of as a score. The overall outcome results in the viewers finding themselves in a quasi endless hall of mirrors, of uncannily similar claims, assertions, and visages, alternating between a boisterous chorus and a single plaintive voice.

The success of MetroPAL.IS. is predicated in the belief that political discourse is best carried out by the personal voice of individuals, not by governments or political entities. Reconciliation is at the heart of MetroPAL.IS., yet ultimately the artist’s intention was to create a layered artwork that resists easy interpretation and defies expectations or preconceived notions as what it means to be an Israeli, or a Palestinian-and a New Yorker, or by extension, an American. The commissioning and presentation of this multiple-channel immersive HD video installation originated with and was supported by the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT. Its presentation at the Benton is supported in part by the Human Rights Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs. Shimon Attie with Vale Bruck MetroPAL.IS., 2011 Eight-channel high-definition video installation Digital video, color, sound; 11:41 minutes Editor and audio post-production: Paul Hill, Wexner Center for the Arts Production Managers: Neta Zwebner-Zaibert and Hilla Medalia (kNow Productions) Field Producer: Jamie Abrahams Commissioned by The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York