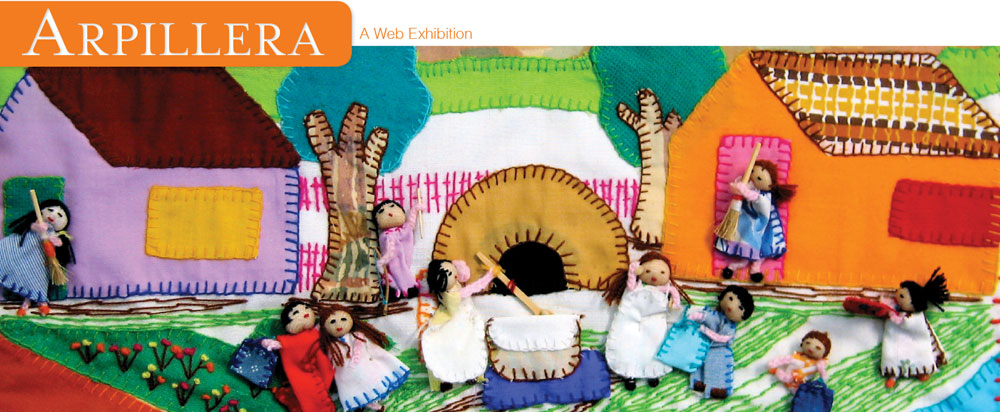

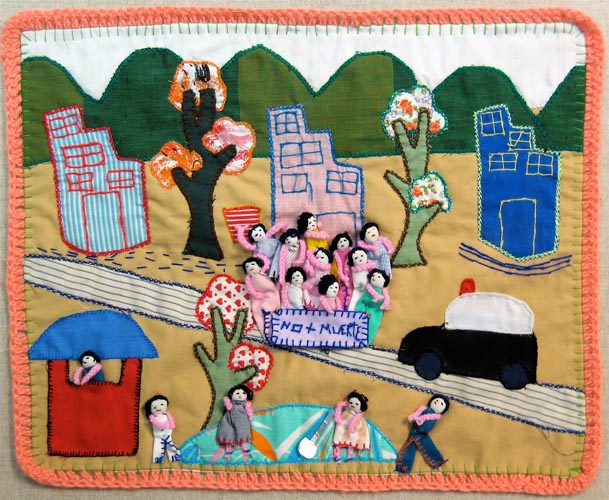

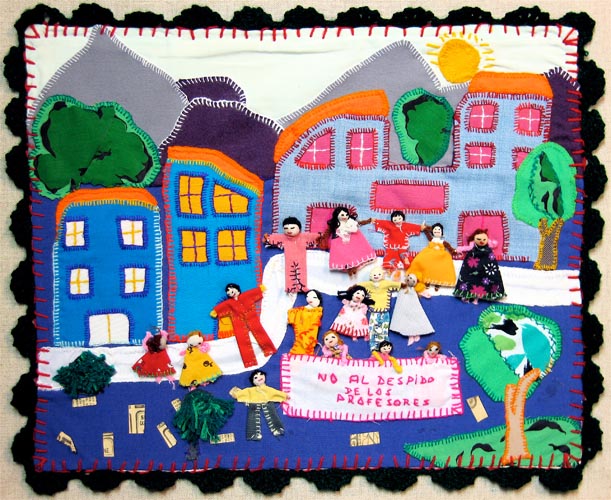

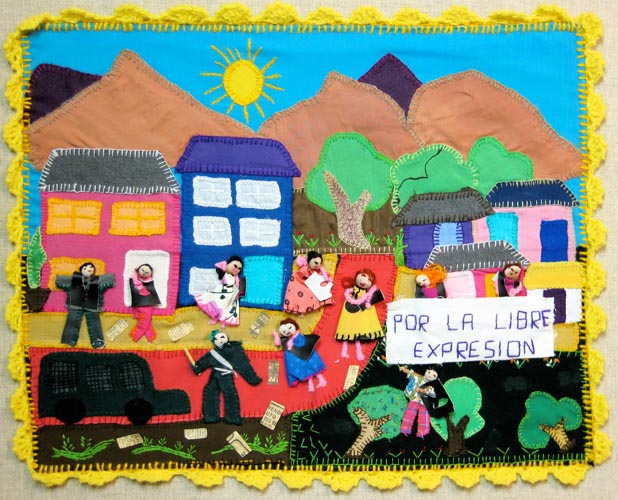

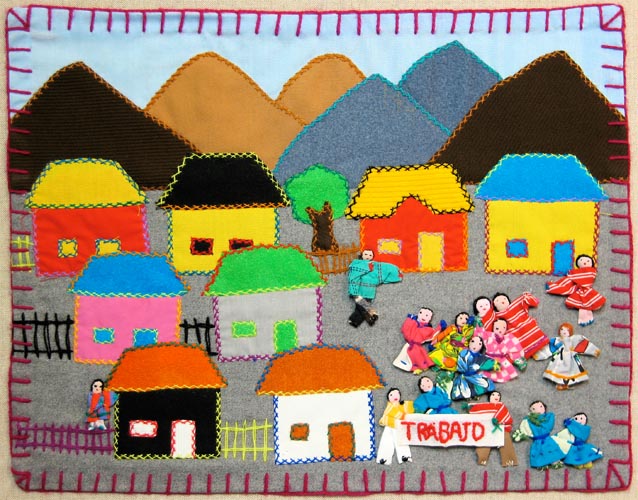

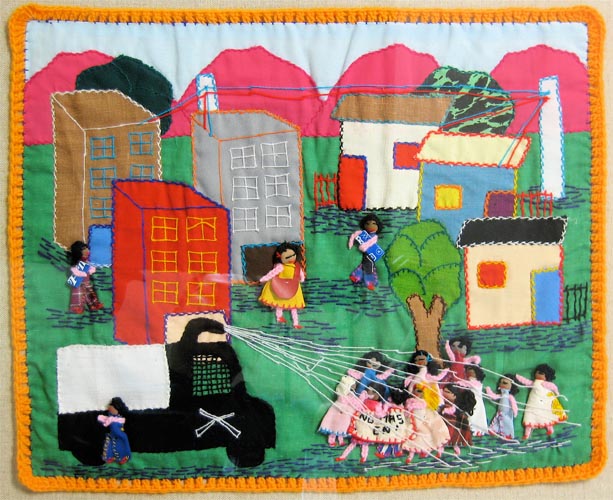

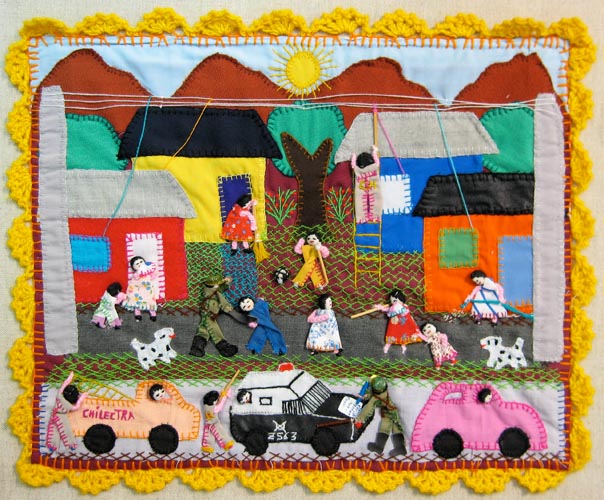

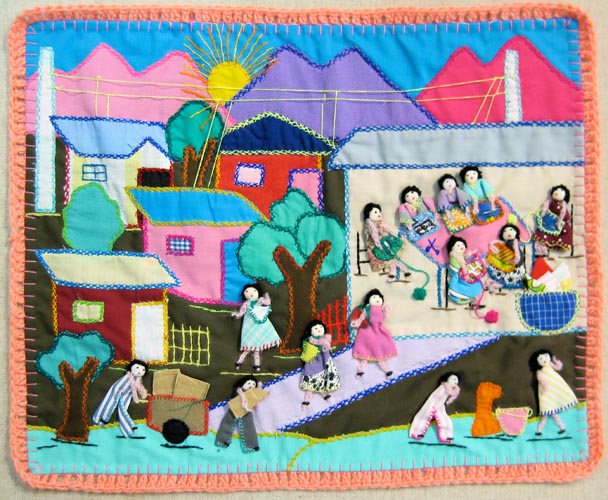

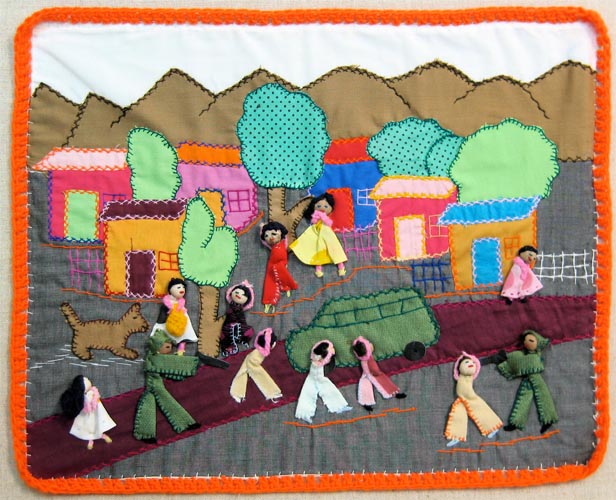

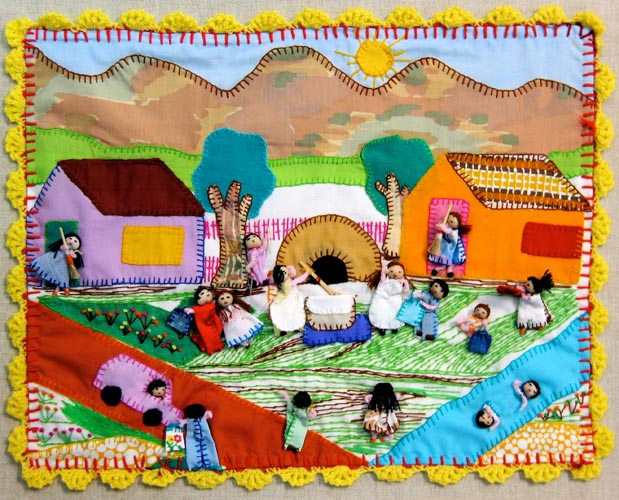

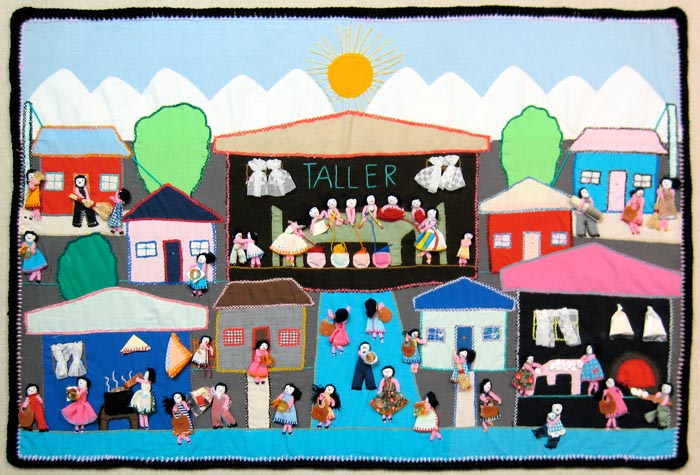

Folk art? Messages of protest? Historical records? Chilean arpilleras (are-pea-air-uhs, burlap in Spanish) are all of these. The brightly-colored patchwork pictures stitched onto sacking are chronicles of the life of the poor and oppressed in Chile in the 1970s and 1980s during the totalitarian military regime of General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte.

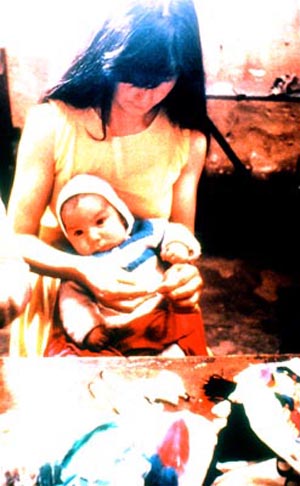

Poor women and women whose husbands, sons, or brothers were killed or imprisoned by the government met each week around crowded tables in one-room workshops on the outskirts of Santiago, where they shared their burdens and stitched small but meaningful tapestries. Their handwork told the outside world of their hunger, fear, unemployment, housing shortages, and their missing men folk who are still referred to in Chile as the “disappeared” and “detained.”

Arpilleras served to document and denounce oppression in a country where all normal channels of free expression were closed. To the women, making arpilleras was a way to share their sorrows and concerns. To present-day viewers, arpilleras are a testament to the women’s extraordinary strength and survival through tremendous suffering and loss.

Once each month, the new arpilleras were collected from each workshop and taken to the Vicaria de la Solidaridad (Vicarate of Solidarity), an ecumenical human rights group of the Catholic Church in Santiago that distributed them internationally. Since the Chilean government considered them traitorous and forbid them to be shown or sold in the country, the earliest arpilleras were smuggled out of the country in diplomatic pouches. Packages and suitcases suspected of containing them were confiscated.

To protect the women, who were known as arpilleristas, their tapestries were generally unsigned, though the Vicaria turned over to them all the profits they received from selling the works abroad. Often, this money was the only income the women had.

Contemporary political unrest brought arpilleras into being, but their roots date back to the 1960s when a Chilean cottage industry began producing decorative embroidery of domestic scenes using brightly colored yarn. But after the coup in 1973, wool was scarce and unemployment was at 25%, partly because relatives of the disappeared and detained were barred from most jobs, so the arpilleristas turned to making fabric appliqu work in the Vicaria workshops, which were organized as support groups. While the earliest arpilleristas were the survivors of husbands, brothers, and sons who had disappeared after Pinochet came to power, shantytown dwellers and other destitute women in and near Santiago later joined in the craft.

Standards for arpilleras developed quickly. At first, arpilleras were the size of a large placemat, about 14″x18″, but later smaller and larger ones were made as well. A mural sized one measuring 6′ square was made from several arpilleras sewn together. Reviewers in the workshops inspected the arpilleras for both quality and content, a practice that was established early. The reviewers were most often women whose design and sewing talents were recognized as superior and who also served as informal teachers. Very likely, the discussions they had with workshop members on technique, design, and theme were helpful.

Themes for the arpilleras were decided weekly by each workshop group. However, each arpillera was the work of an individual who developed the design at the workshop, continued sewing on it at home, and brought the finished piece to the next meeting. Each workshop generally had about twenty women. Each woman was allowed to make just one arpillera a week unless her need for money was so great that the group decided she could make two. More than 250 Chilean women became arpilleristas during the time.

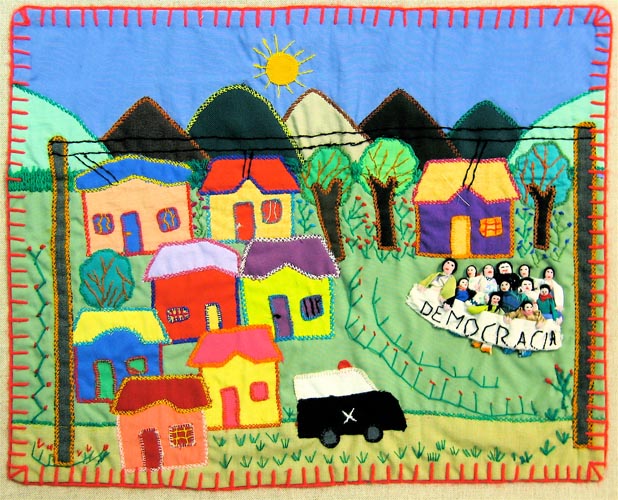

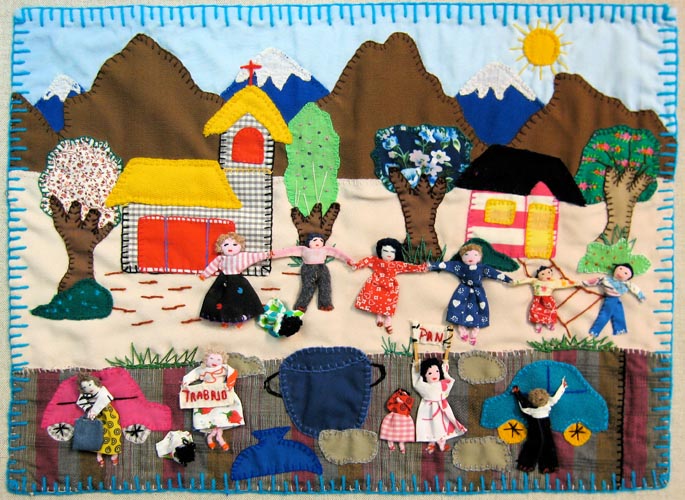

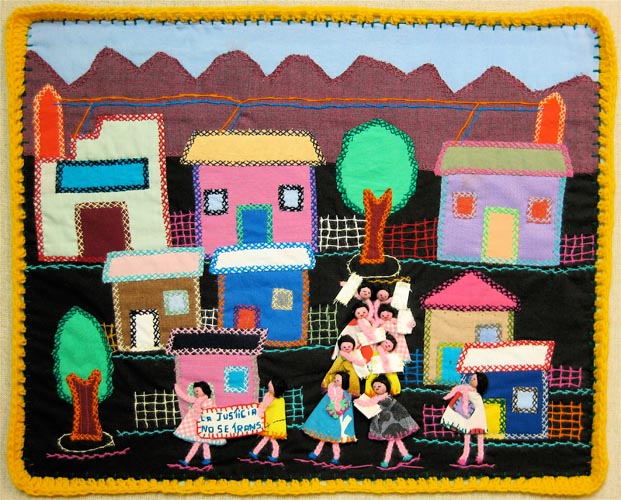

The Vicaria established a few rules for the workshops with regard to what could and could not be shown in the designs. Explicit scenes of torture, for example, were prohibited, as were other frankly political or “too strong” themes, as the Vicaria termed them, icons that might provoke the government to arrest or harm the arpilleristas. The only words allowed on arpilleras were those that would normally appear in reality, as on banners carried by protesters or names on buildings and sides of trucks. Traditionally, the Andes Mountains were depicted in the background, confirming that the stories took place in Chile.

Arpilleras have many common elements. Bits of fabric are cut in the shapes of houses, trees, or objects and are stitched to the backing. Figures of people are almost always three-dimensional, with little rolled arms, heads and bodies coming out of a flat background. Sticks, bits of foil, plastic, or paper, dried beans, and other commonly found materials are frequently sewn or glued onto the tapestries. Simple decorative topstitching fills in the details. Each arpillera is bordered by a colorful fabric binding, blanket stitch, or crocheted wool edging. Older women with failing eyesight helped by stuffing the heads for the figures and crocheting the borders.

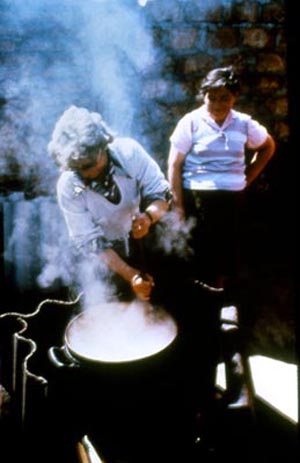

Certain images appear over and over. Big black kettles sitting on fires represent the community soup pots (ola comun) that Chilean churches provided in Santiago’s “hunger zones.” Also frequently seen are the cooperative bakeries and laundries that were organized to help the poor survive, as well as the arpillera workshops (talleres). Many arpilleras show children standing in milk or clinic lines, washing cars or scavenging for cardboard to sell. Bands of protesters are seen carrying banners or distributing political flyers, both of which were illegal acts. The national militarized police appear frequently, wearing dark uniforms and driving tank- like vehicles. Threads spilling out of a nozzle can represent the water that poor women got from a community pump for their daily needs or the contaminated water that was sprayed on protesters by militia determined to break up a street demonstration. Other threads represent electric lines that people hooked up illegally from their houses to the main power lines in order to steal electricity after the government shut theirs off. The dangerous practice of hooking up happened every evening, and the unhooking was done every dawn since people feared arrest more than accidental electrocution. Doors of factories and hospitals have big X’s stitched on them to indicate that they were closed to families of the disappeared or detained.

It’s important to note that the arpilleristas had no training in art. Some were definitely talented, and some had distinctive ways of portraying trees, mountains, or houses that made their work recognizable. While the tapestries rarely show technical sophistication, they more than make up for it in their powerful sense of design, strong colors, and gripping subject matter. Small as the images are, they speak simply and movingly about particular events and the daily hardships of Chilean life.

It should be said that not every arpillera depicts soup kitchens, demonstrations, arrests, or candlelight vigils for executed political prisoners. Some show life as the arpilleristas might have wished it waswith thriving markets, good health care, happy children, and a peaceful countryside. In fact, it can be argued that all Chilean arpilleras expressed hope for a better future, with the sun rising over the Andes, bringing a new day.

Once a foreign market for the tapestries was established, arpilleras from other sources began to appear in the marketplace. Some women, along with some men, who believed that the arpilleras that came out of the Vicaria workshops were too timid in their themes, produced arpilleras with strong political themes. By contrast, these government-sanctioned workshops of women loyal to the dictatorship produced propagandizing arpilleras, filled with happy themes depicting Chile as a prosperous country with benevolent rulers.

Over time, people in other Latin American countries adopted arpilleras as an art form. Among them were Peru, where some believe their three-dimensional doll-like figures are said to have originated, as well as Colombia and Nicaragua. Their arpilleras almost always depict an innocent, happy world.

Chilean arpilleras became an influence on fine art in Chile where artist-printmakers were inspired by their imagery and design. An exhibition of their prints in Santiago was firebombed by the militia in the 1980s. A few of the prints reached the United States.

It’s clear that the arpilleristas of Chile ultimately learned the delights of creating art. As these oppressed women turned to sewing for solace and income, they grew more self-confident, thoughtful, and independent, and learned of the pleasure to be found in color, texture, shape and form. By telling their painful stories fearlessly and truthfully, they became citizens of a world larger than anything they or their mothers had ever known. It is no wonder that their arpilleras have been called “the revolutionary banners of modern Chile.”

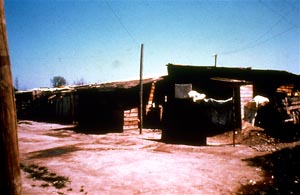

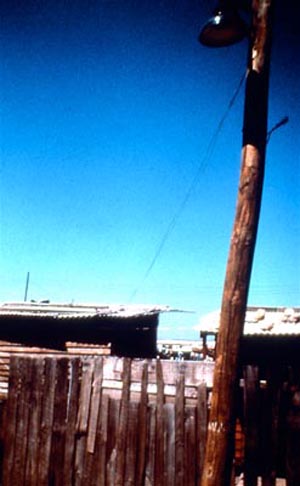

These 20 slides of scenes in Chile show how vividly the arpilleras reflected the world that the arpilleristas sewed into their patchwork tapestries. The Benton Museum is grateful to Professor Hernan Vera, a Chilean who teaches at the University of Florida, Gainesville, for making these images that he photographed in his homeland available to us and (on a loan basis) to you.

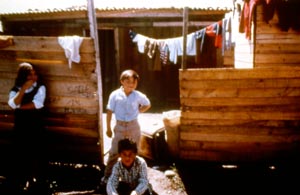

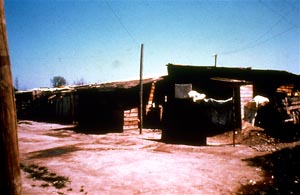

Shantytown houses in the outskirts of Santiago,

Chile, where arpilleristas live.

Shantytown houses in the outskirts of Santiago,

Chile, where arpilleristas live.

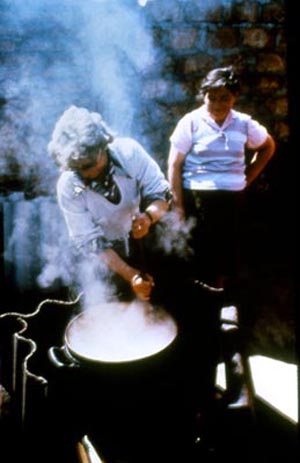

“Common pots” and soup kitchens

“Common pots” and soup kitchens