September 4-October 14, 2012

Reception: Thursday, September 6, 5-7:30 pm

The Evelyn Simon Gilman Gallery

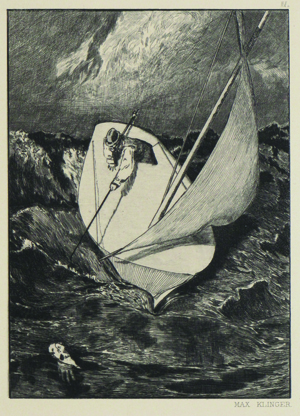

“The dark side of life” is a quote from the German artist Max Klinger (1857-1920) when comparing painting to the graphic arts. Klinger said that the black and white abstraction of the graphic arts was better suited to depicting the emotional and social realities of contemporary life than the coloristic optimism of painting. His work embodied this dichotomy as did that of his fellow artists Alfred Rethel (1816-1859) and Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). During the latter half of the 19th century, all three created narrative cycles of thematically related works in print media that dealt with the realities of life directly and indirectly. Their picture stories, as a genre of storytelling, were hardly new, and their most immediate predecessors were from the 18th century: William Hogarth’s “modern moral tales” and Francisco Goya’s Caprichos and Desastres. The three 19th-century artists confronted contemporary society with narratives about the consequences of societies deeply divided by class and economics or with imagery that dwelled on individual psychology.

Rethel’s Another Dance of Death (Auch ein Totentanz, 1849) is the best-known visual commentary on the revolutionary events in Europe in 1848. While the title of the six woodcut images is based on Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dance of Death published in 1538, Rethel’s image of Death is as a seducer of the lower classes to riot to subvert the social and political order, but their actions result only in death and destruction. The thrust of Rethel’s visual commentary is reactionary and anti-republican, and has little sympathy for the lower and middle classes. His imagery, however, is both powerful and sarcastic, and found such a huge audience that the number of folios printed between 1848 and 1849 ran into the thousands.

Käthe Kollwitz’s 1897 narrative cycle The Weavers’ Revolt (Ein Weberaufstand) stands in striking contrast to Rethel’s position. Based on Gerhart Hauptmann’s 1893 play The Weavers (Die Weber), the narrative relates in generalized terms the events of an equally abortive revolt by Silesian weavers in 1844; an uprising that again leads only to death and destruction and not to change. Kollwitz’s sympathies, however, lie with the peasant workers and the intensely difficult economic circumstances under which they lived. Both Rethel’s and Kollwitz’s narratives serve political ends, and their differences reflect the increasingly complex social picture of 19th-century Europe.

Max Klinger, like Rethel and Kollwitz, focused on the “dark side of life,” but for him it was more the individual than the social group. By “dark side,” Klinger meant psychological figments of the imagination, the sordid and the abnormal, the good and the bad of reality and of the psyche. In varying degrees these qualities are seen in Klinger’s narrative cycles that carry titles like Eve and the Future, Dramas, A Life and On Death, Part I and Part II. The most famous of his narrative tales and the most psychologically complex, however, was the cycle of ten etched plates comprising his 1881 story, A Glove (Ein Handschuh), which centers on the psychological turmoil of the protagonist who has found and kept the dropped glove of an unknown and beautiful woman. This sexual and fetishistic fantasy resonates in the 20th century, and it predates Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams by two decades.

Besides these three folios, two other narrative series by Klinger and Kollwitz are presented in “The Dark Side of Life.” The five sets together represent the emerging interest in 19th-century Europe in narrative series that thematically engage the modern world and whose visualization does not rely on religious or mythological premises. Rather the modern world is seen in an unconventional and oft times searing light.